Estonian way to independence and reactions of Baltic Germans

The original version of blog post in Estonian: “Eesti iseseisvus” — ilus sõna, hiilgav soov ja tore unistamine. Baltisakslaste vaade Eesti iseseisvusele

The declaration of independence, which was publicly read out in the name of the Council of Elders of the Provincial Assembly in Tallinn on February 24, 1918, had little meaning in the eyes of Baltic Germans. The next day German troops entered Tallinn and Baltic Germans hoped to use their help to unite Estonian territory as a part of a Baltic duchy under the German Kaiser. Baltic noble corporations working hard and enthusiastically on the project of a new Baltic duchy tried to engage, at least formally, also indigenous people in the activities of the Land Council of the Baltic Duchy in order to present its decisions as the will of all inhabitants.

In November, the German provisional government’s representative in the Baltics handed over power to the Estonian Provisional Government, which was a serious setback for the supporters of the idea of a Baltic duchy. The Baltic Germans, however, did not give up their idea to unite these territories with the German state in the near future and used different means to achieve their goal: they joined the ranks of Landeswehr formed by the Baltic Regency Council, established their own party and actively participated in the elections of the Estonian Constituent Assembly.

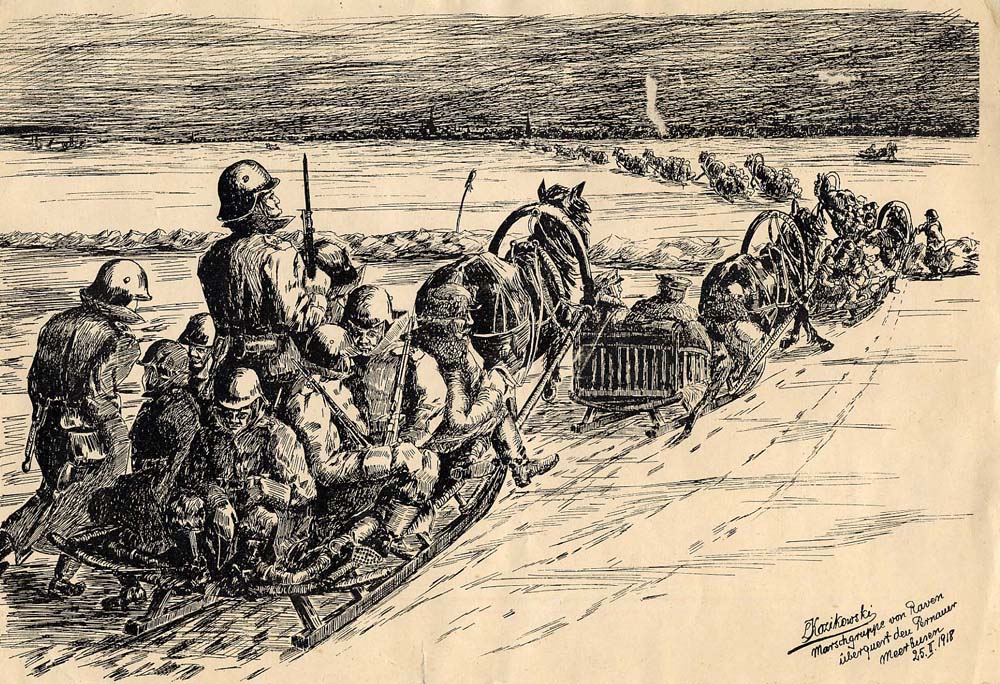

In mid-February, the peace negotiations between Soviet Russia and Germany in Brest-Litovsk had temporarily broken down and on February 18, 1918, Germany started the offensive Faustschlag in order to re-establish order in the eastern territories. Three German army groups advanced towards Estonia: the 60th army corps from Düna moved to the north and took Tartu on February 24th and the 6th corps moved to Pskov. On February 19, the 68th army corps started an offensive from the islands and crossed the ice-covered sea. Its advance-guard reached the mainland the next day. The remnants of the Tsarist army did not resist the advancing German troops, but the Red Guard units had several serious clashes with the invaders.

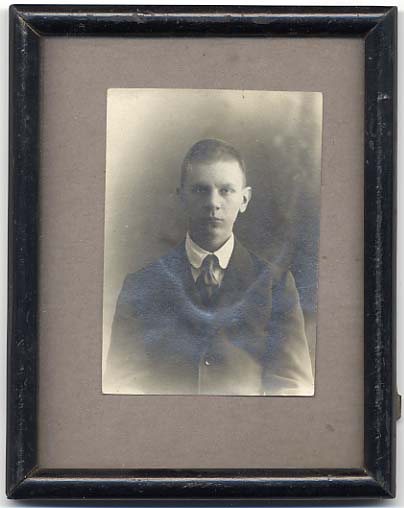

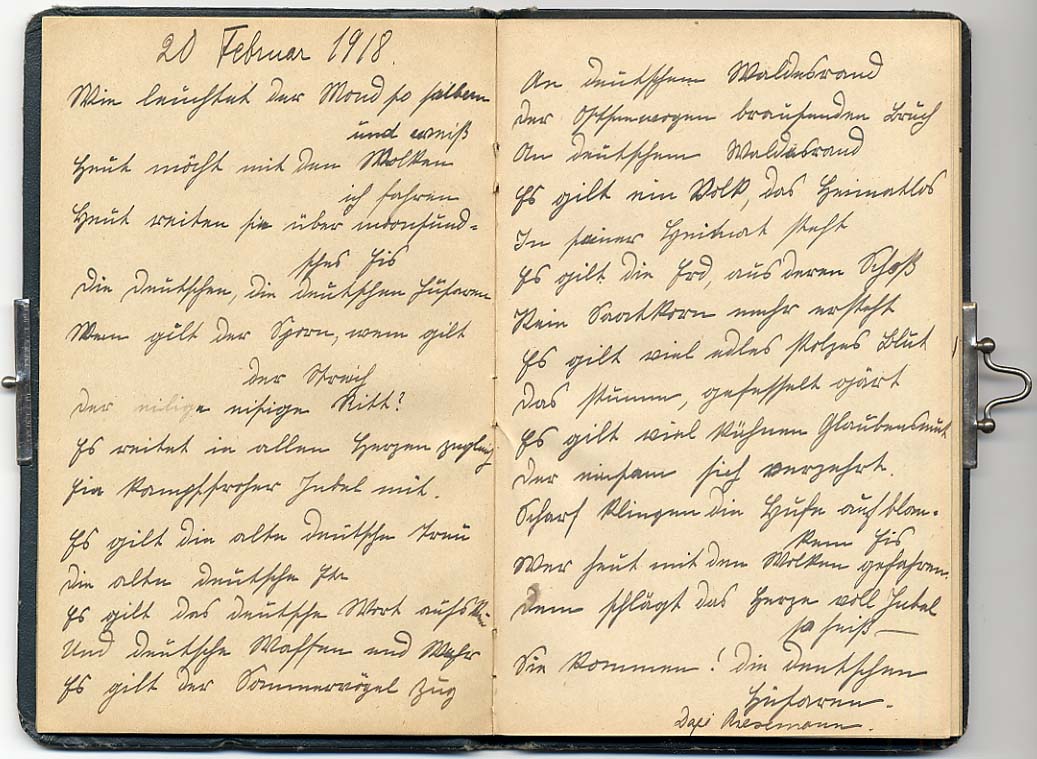

February 20, 1918

Dafi Riesemann’s poem which Julie Therese von Ungern-Sternberg (born 1871, nee Dellingshausen) wrote in her album on February 20, 1918.

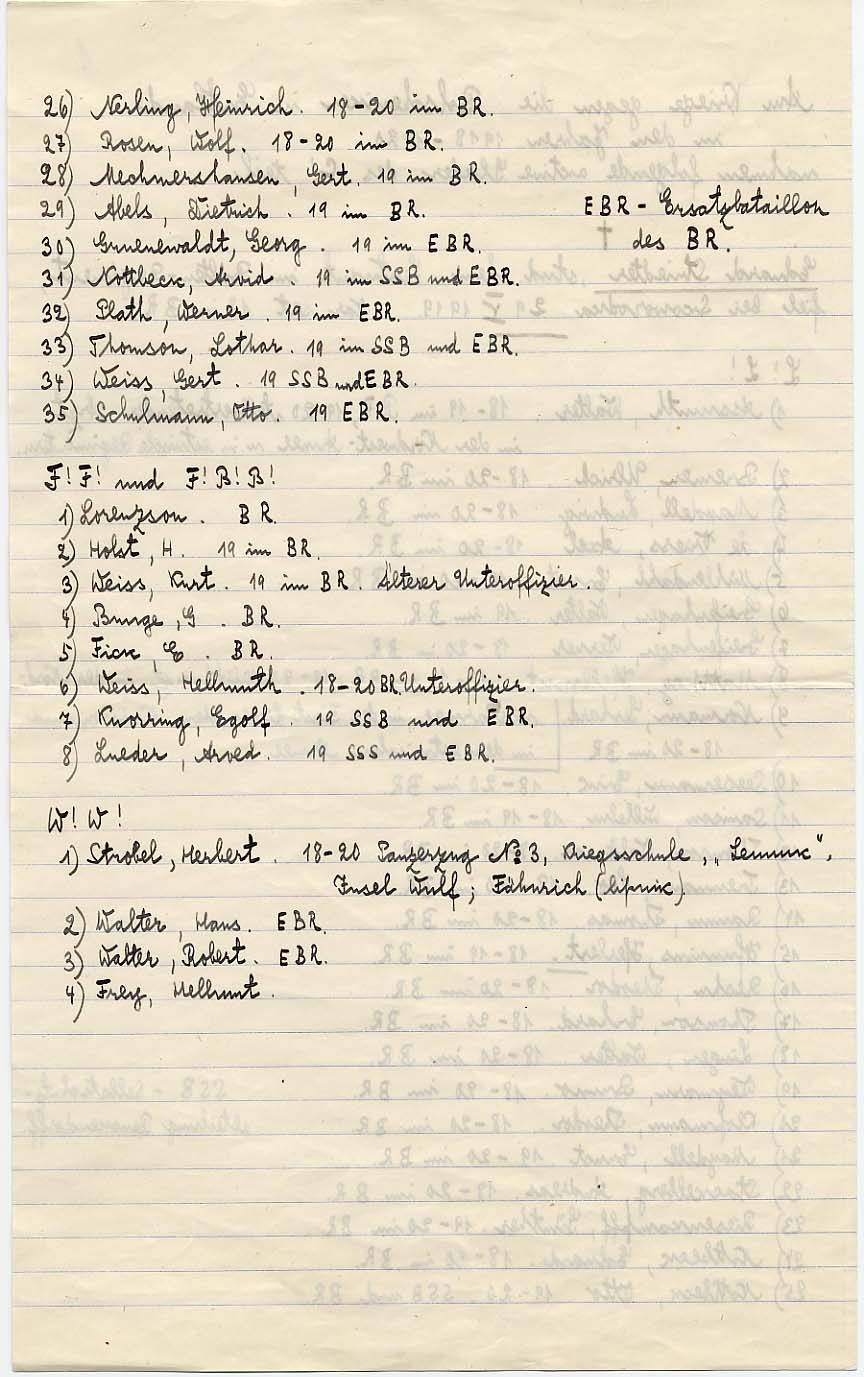

His son Nils Nikolai von Ungern-Sternberg joined the Baltic Battalion at the end of 1918. RA, EAA.1423.1.142

The arrival of German troops brought not only the occupation regime. The Estonian Salvation Committee used the short break between their arrival and the departure of Russian troops to declare Estonian independence.

February 24, 1918

The last head of the Estland noble corporation Eduard von Dellingshausen expressed his opinion about the proclamation of independence in Tallinn on February 24th:

This proclamation only a few hours before Tallinn was liberated by the German troops was possible only because the Bolsheviks had fled the advancing German troops and it was meaningless … (p. 189)

He continued:

One should never forget that the occupation by German troops in February 1918 took place with the help of the noble corporation and at their initiative against the will of the Estonian Council of Elders, but without this period Estland and Livland would have sunk into a quagmire of Bolshevism and there would not have been any sovereign Estonian or Latvian states but the Bolshevist-Asiatic-Russian chaos would have taken upper hand.

(p. 216)

Im Dienste der Heimat! Erinnerungen des Freiherrn Eduard von Dellingshausen ehem. Ritterschaftshauptmanns von Estland. Stuttgart, Ausland und Heimat Verlags-Aktiengesellschaft, 1930

March 1918

On March 10, 1918, rural township elders from Southern Estonia that were forced to participate at the meeting of Livland representatives in Riga signed a protest against the idea that they represented the entire country, stating that the only body which could act as a legal representative of the whole population is the Provincial Assembly (Diet) of the Estonian Province established on the basis of the 30 March 1917 decree of the Russian Provisional Government. The elder of Vana-Antsla township Peeter Koemets read out this statement. This statement was not recorded in the minutes, and in the name of the German occupation troops the chair of the meeting – Baron Stael-Holstein – did not allow them to leave the meeting hall.

The Land Councilor of Livland informed the Land Council of Ösel on March 23rd:

According to the resolution of the Livland Diet, a land council will be convened in Riga on April 10th and it will comprise following representatives:

32 manor lords and the same number of rural townships, four of the noble corporation, eight pastors (deans), ten of towns except for Riga and one of Tartu University. The deputies will decide the separation of Livland from Russia and elect 24 delegates to a united land council of Estland and Livland which will be held on April, 12th. Delegates of the Ösel noble corporation, manor lords, community elders, the towns of Riga and Kuressaare and pastors are invited there.

April 1918

A memorandum by the Livonian Public Benefit and Economics Society to the occupation authorities in April 1918 claimed that “favourably disposed” local Estonian leaders could be involved in the administration of the country.

The Estonian leaders that were engaged with the resolution, partly devoted to the utopia of the independent Estonian Republic, have been left aside since they cannot be attracted to our side and at the moment it is important to involve favourably disposed local Estonian leaders. There are such people. They are actively working on a new newspaper which would be edited in German mind. The absence of the renowned leader [Jaan] Tõnisson — he and his followers are having negotiations with Englishmen in Stockholm in order to achieve English protectorate for the Estonian state in the future and English funding— has very favourable impact as many are happy now to remove him from power.

The leaders of the most important Estonian agricultural societies can be named German-minded: in their opinion, collaboration with the manor lords is the only opportunity to protect themselves from the revolutionary and democratic elements. We have contacts with them but these definitely have to be intensified by providing them with agricultural equipment, iron, fertilizers and other consumer goods. In this way, the favourably disposed leaders could secure support for themselves [among locals].

Extract from the appendix to the resolution of the Baltic land council (Landesrat) dated April, 12, 1918.

A brief overview of the Baltic legal and administrative order is followed by the depiction of the new legal situation resulting from the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty of March 3, 1918. Local political sentiments were then considered:

Almost all local people in Estland and Livland have wished separation from Russia. […] A massive movement started […] in short — all the organizations in the country strongly expressed a unanimous shout: separate from Russia and unite with Germany.

It has been the wish of all people; not a single objective observer can doubt that. Only two small groups spoil the ‘general harmony’ in the country: Bolsheviks and Estonians ‘bought and paid-for’ by Englishmen.

Baltic Germans could not understand that Estonian independence was not an adventure of a small group of English-minded agents bought by English money but the real wish and will of the majority of Estonian people.

May 1918

On May 10, 1918, Frankfurter Zeitung published the reply of the secretary of the Estland noble corporation Otto von Schulmann (1888–1964) to the statements of Estonian politicians published in the same newspaper on March 28th and May 4th.

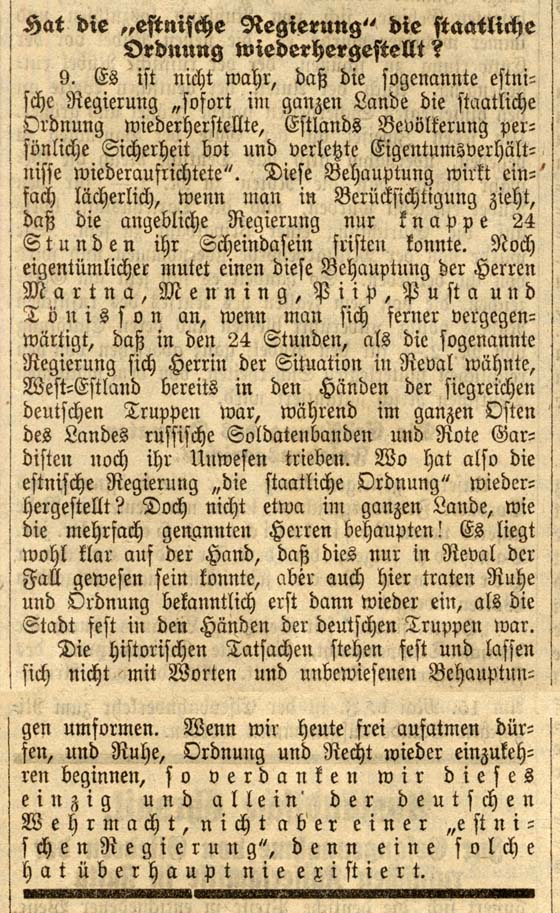

Did “Estonian government” restore public order?

It is untrue that the so-called Estonian government restored immediately public order in the whole country, provided security for the Estonian inhabitants and reconstituted the property relations distorted [by the Soviets]». This claim is ridiculous given that the so-called government did not exist longer than 24 hours. The statement by Messrs Martna, Menning, Piip, Pusta and Tõnisson is even stranger if one knows that western Estonia was in the hands of victorious German troops while the eastern part of the country was harassed by Russian soldiers and Red Guard, all during the 24 hours in which this so-called government believed itself to be in power in Tallinn. Where did this Estonian government restore “public order?”. Not in the entire country, as the repeatedly mentioned gentlemen claimed! It is obvious that it could be so only in Tallinn although even here peace and order were restored only after German troops had taken firm grip of the city.

Historical facts are clear and they cannot be changed by words and baseless claims. If today we can sigh with relief and see peace, order and justice returning to the country, then we can be thankful only to the German Wehrmacht and not to some kind of “Estonian government”, which actually never existed.

Dream of a Baltic duchy

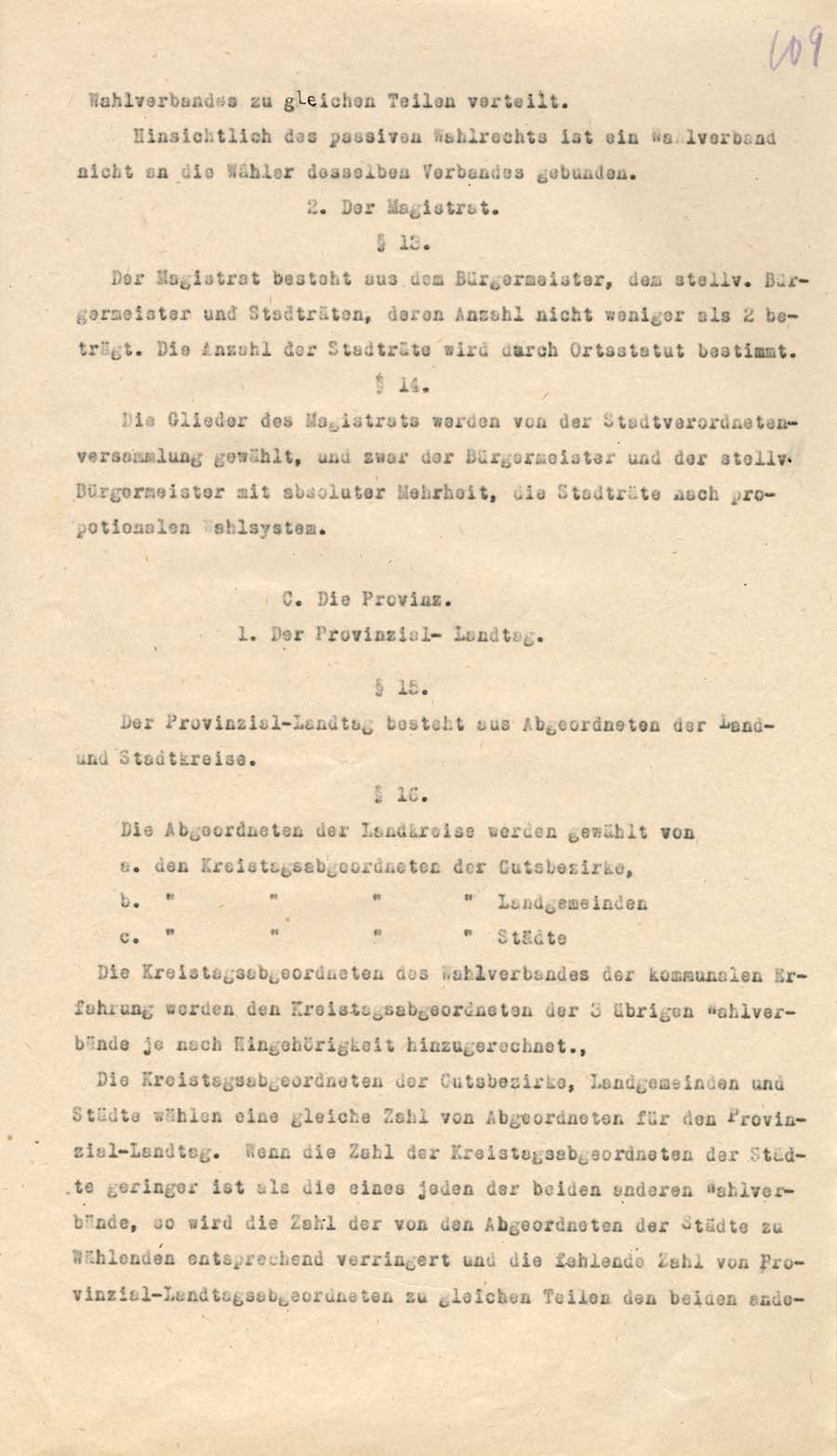

In October 1918, the Baltic Duchy’s constitution drafted by the united land council of Estland and Livland was ready.

It described the governmental order at local (county, city and province) and state level. The highest representative body consisted of two chambers – Senate and the Baltic Diet and the state was ruled by a monarch.

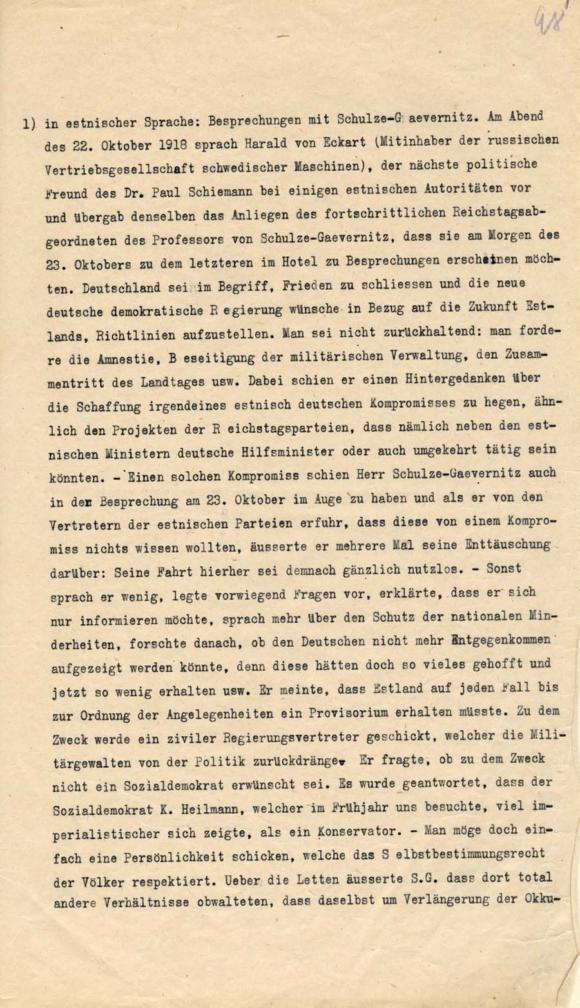

In mid-October 1918, the occupation authorities became more tolerant towards Estonian nationalists. On October 23, 1918, a delegate from the German Reichstag, Professor von Schulze-Gaevernitz entrusted with a broad mandate, visited Tallinn and tried to reach a compromise with the leaders of all Estonian political parties, J. Poska, J. Jaakson, K. Konik, O. Strandman and N. Köstner, on the question of joint Estonian-German government. Among other things he took interest in the question if Estonians would be more forthcoming towards Germans since they have hoped so much and now have got so little.

He disappointedly described his visit to Tallinn as futile.

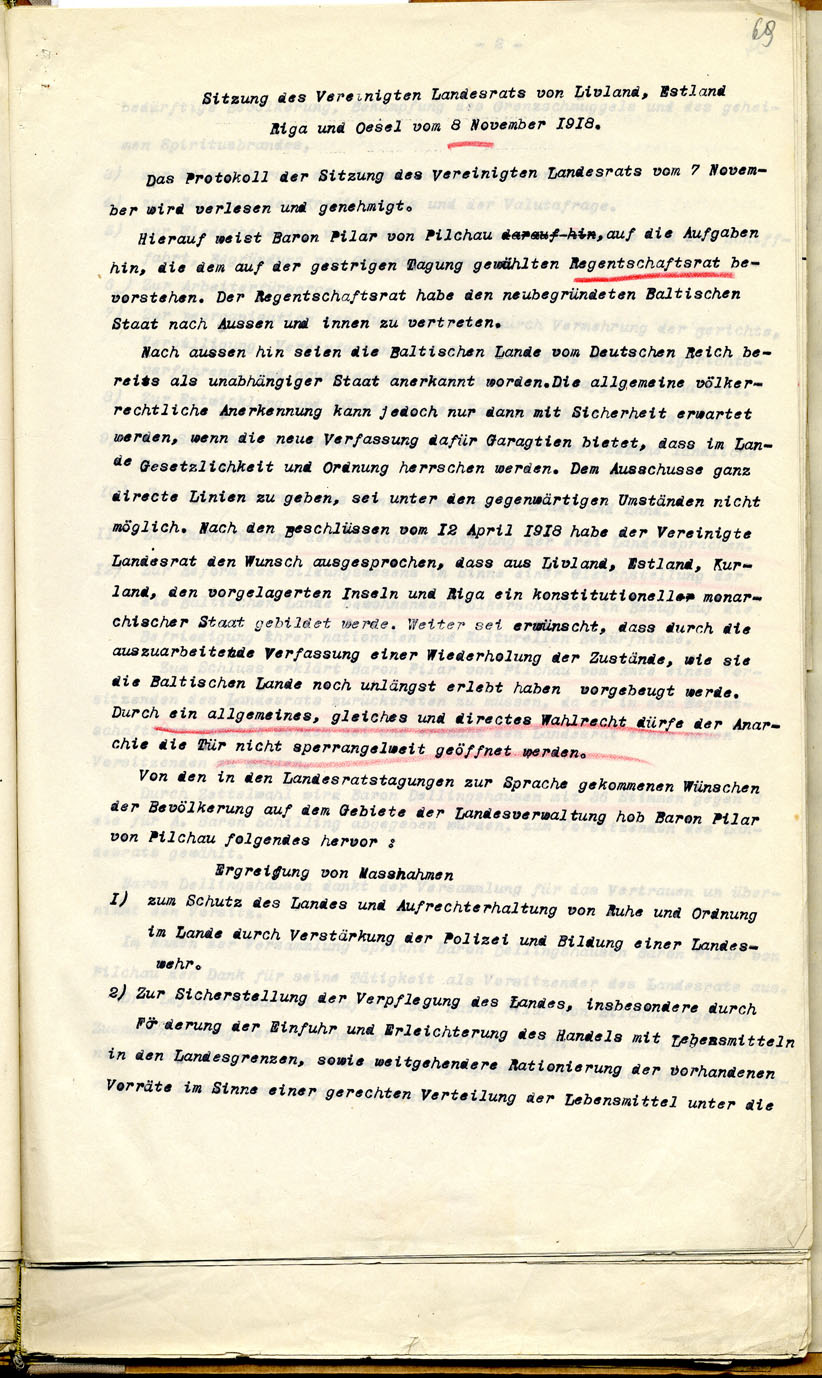

The Baltic lands were nominally recognized as a sovereign state by Emperor Wilhelm II on September 22, 1918. In order to secure peace, lawfulness and order a military unit called Landeswehr was formed. While the Duchy’s time of existence remained fairly short, its official army comprising Baltic Germans, German volunteers and Latvians held on longer. In the Landeswehr War waged from June, 5 to July 3, 1919 the Estonian army defeated this German army group, which posed a serious threat to Estonia’s independence. As a result of Landeswehr’s defeat, the politically and militarily weak Latvian Republic could gain strength.

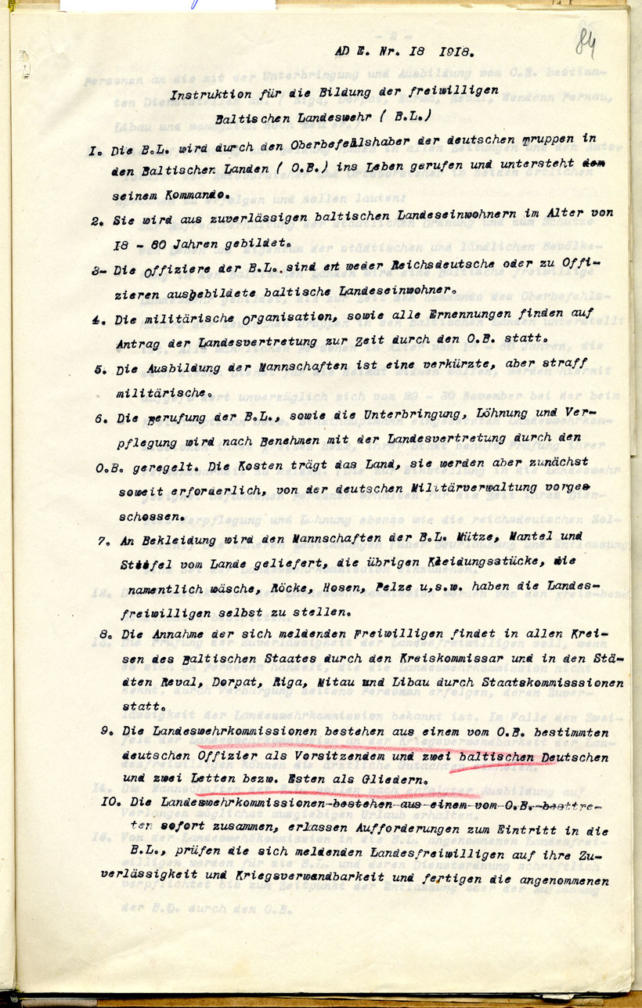

The decision of the Land Council of Livland, Estland, Riga and Ösel of November 8, 1918, to form Landeswehr and respective instructions.

June 1919

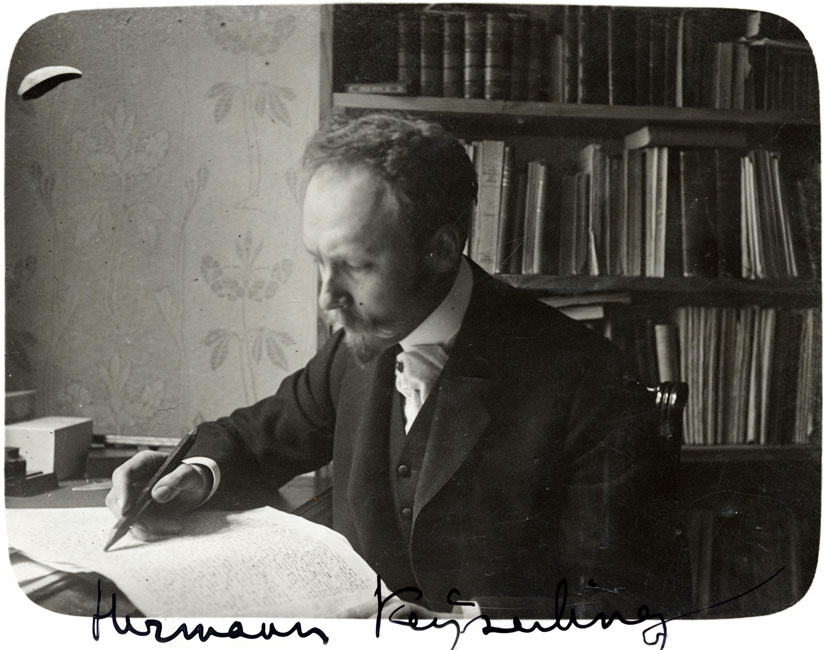

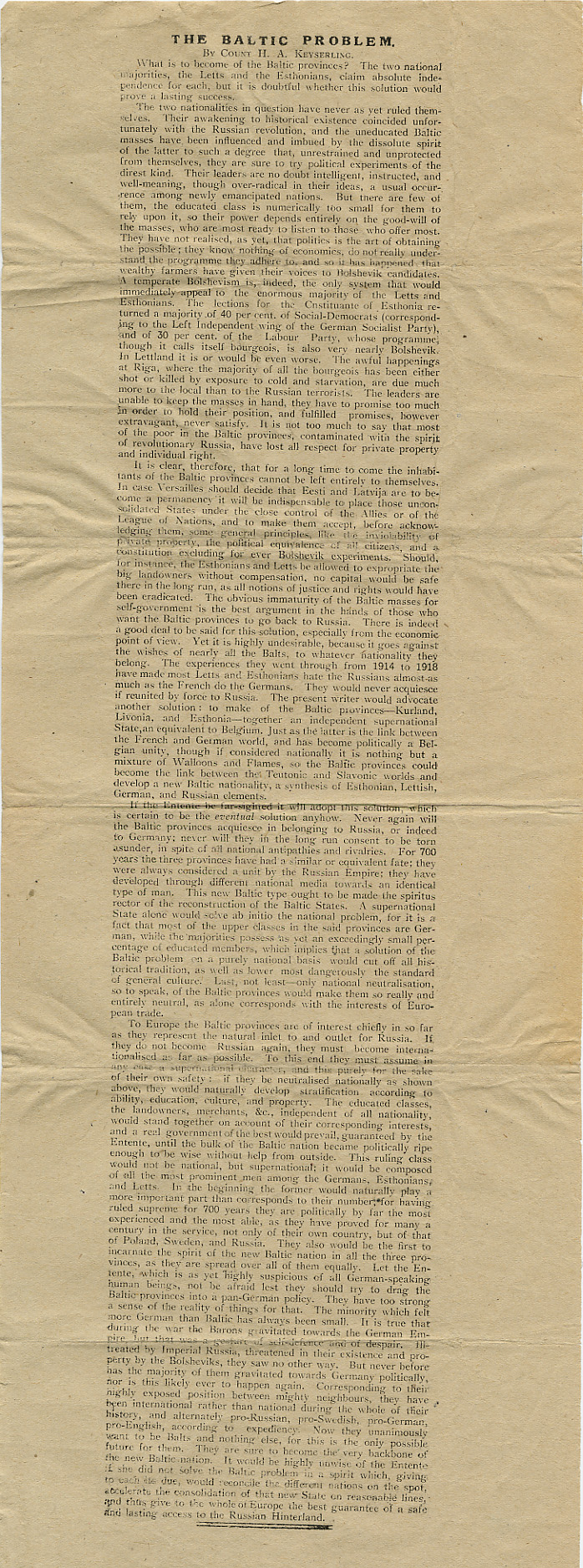

Baltic German philosopher, lord of Raikküla manor, Hermann Keyserling published the article “Baltic problem” in The Westminster Gazette on June 18, 1919.

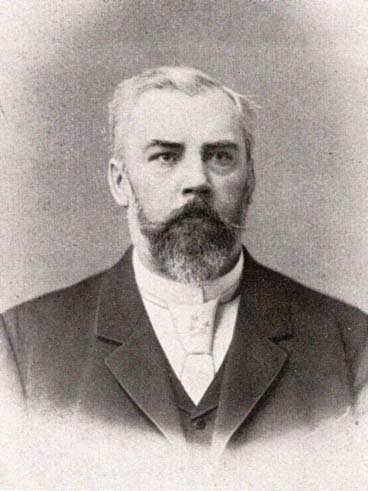

Hermann Keyserling (1880–1946). RA, EAA.1850.1.554

Keyserling sent this text already in spring 1918 as a memorandum to the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to forward it to the British delegation at the Paris peace conference. The article promoted the hope of Baltic Germans evoked after the failure of the Baltic duchy — a united Baltic state with Baltic Germans playing the leading role. He claimed that Estonians and Latvians had too little expertise in economics and politics and therefore he considered it reasonable to establish a Baltic state on the example of Belgium. This would unite Germans, Estonians and Latvians and create a bridge between the Teutonic and Slavic worlds. Given that both indigenous peoples have an insufficient number of intellectuals, the Germans as an upper class would keep culture on a high level and form the backbone of the new ‘nation’.

RA, EAA.854.2.1417

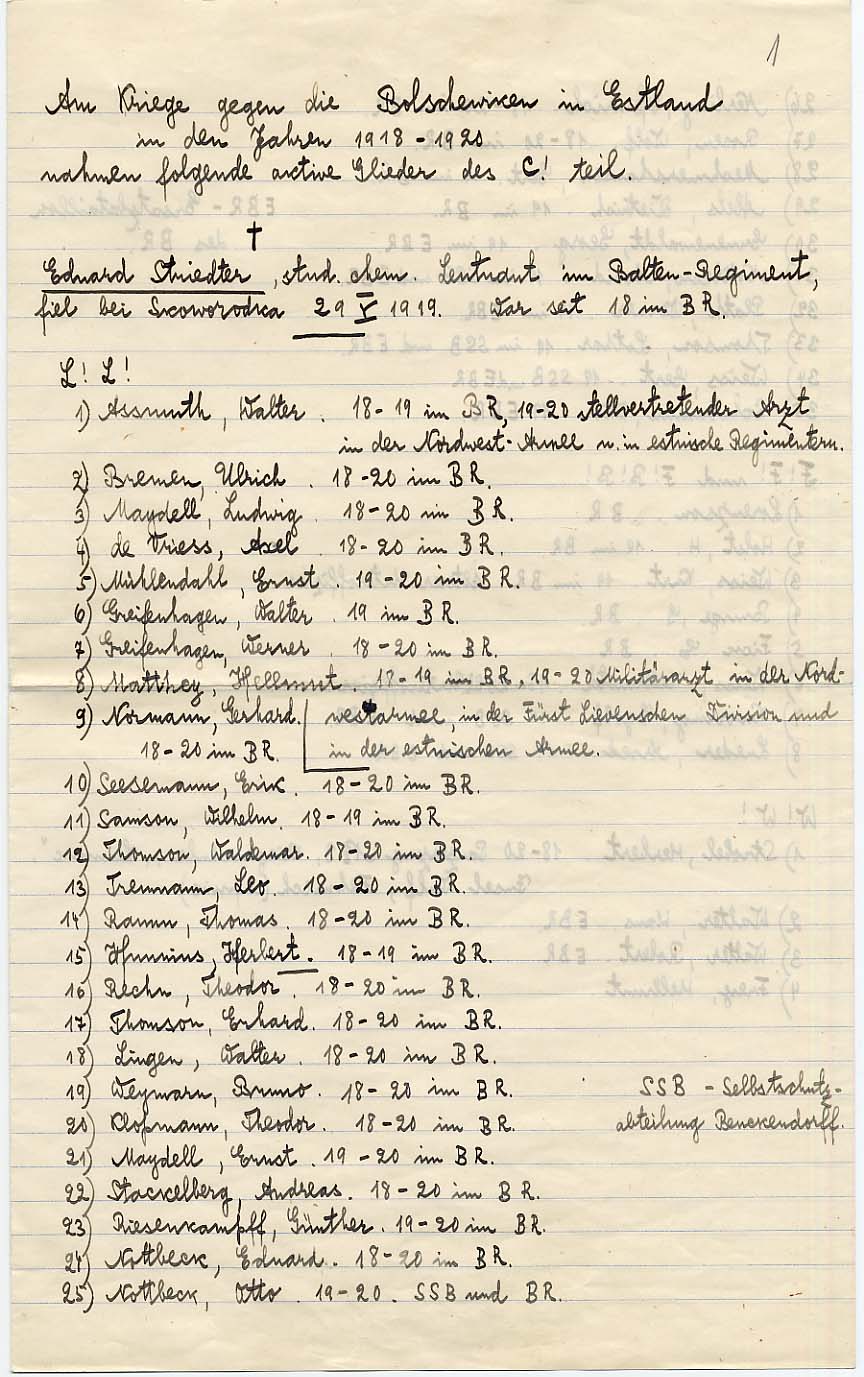

Baltic German volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence

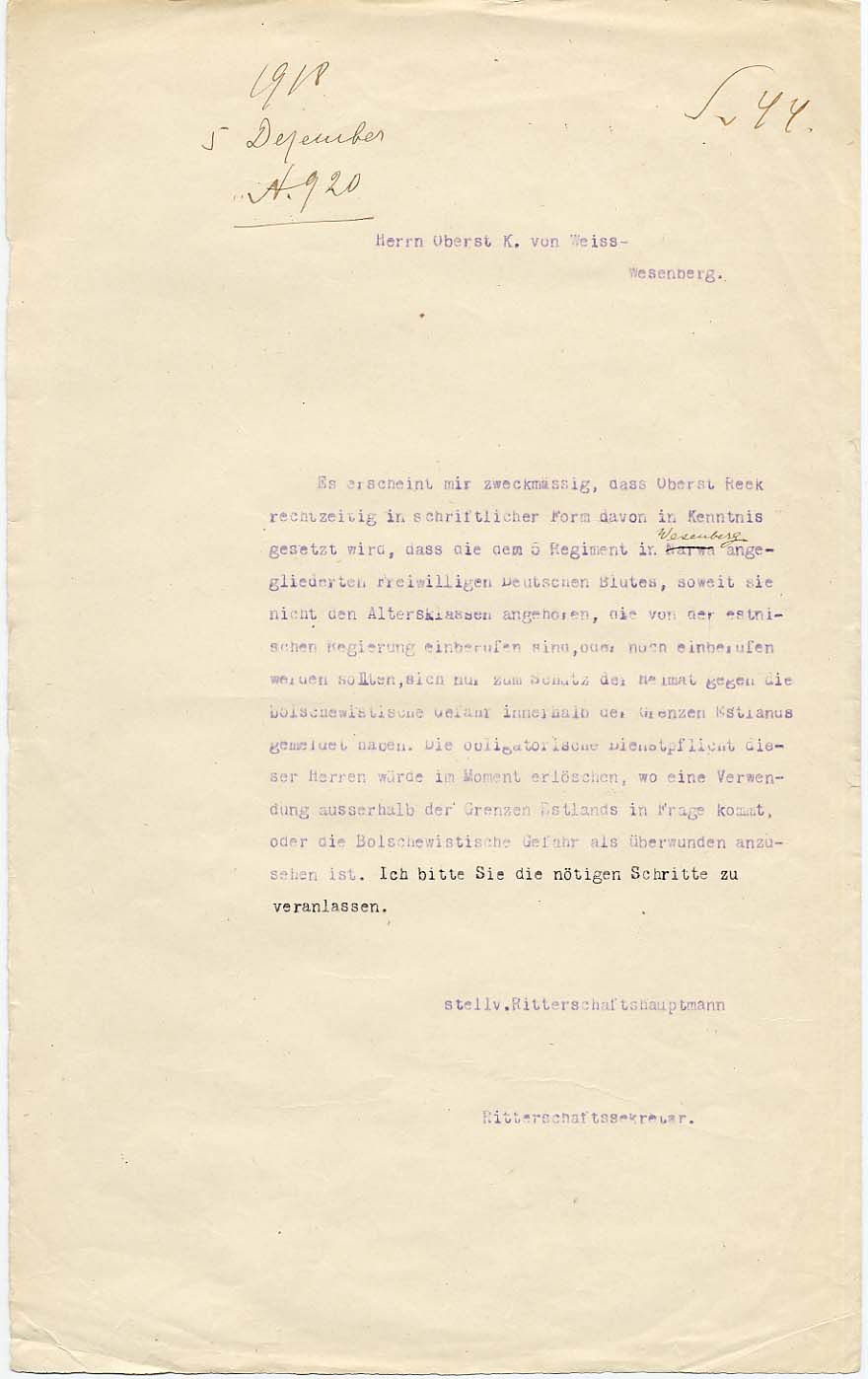

On December 5, 1918, the envoy of the head of Estland noble corporation suggested Colonel Constantin von Weiss that led the Baltic-German Mounted Machine-Gun Commando to let Colonel Nikolai Reek sign a written confirmation that the men who had joined the Commando and volunteered for the protection of the homeland against the Bolsheviks will be used only on the Estonian territory.

Several Baltic German teenagers joined the Battalion in their school years. The men serving in the unit were of very different backgrounds. 10–15% of them were noblemen and manor owners, but most of the enlisted men were from the middle class. In German, the Battalion was called a regiment – Baltenregiment.

Baron Nils Nikolai von Ungern-Sternberg (1900–1940) was born on Essu Manor in Virumaa and had started to study at Tallinn Ritter– and Domschule in 1912. In his CV he mentions that he left school because of war. In 1918, the Reds deported Ungern-Sternberg to Siberia. Having come back to Estonia, he was recruited to the Estonian army (1918–1920). After the war Ungern-Sternberg studied zoology at the University of Tartu and defended his doctoral thesis in Giessen in 1930.

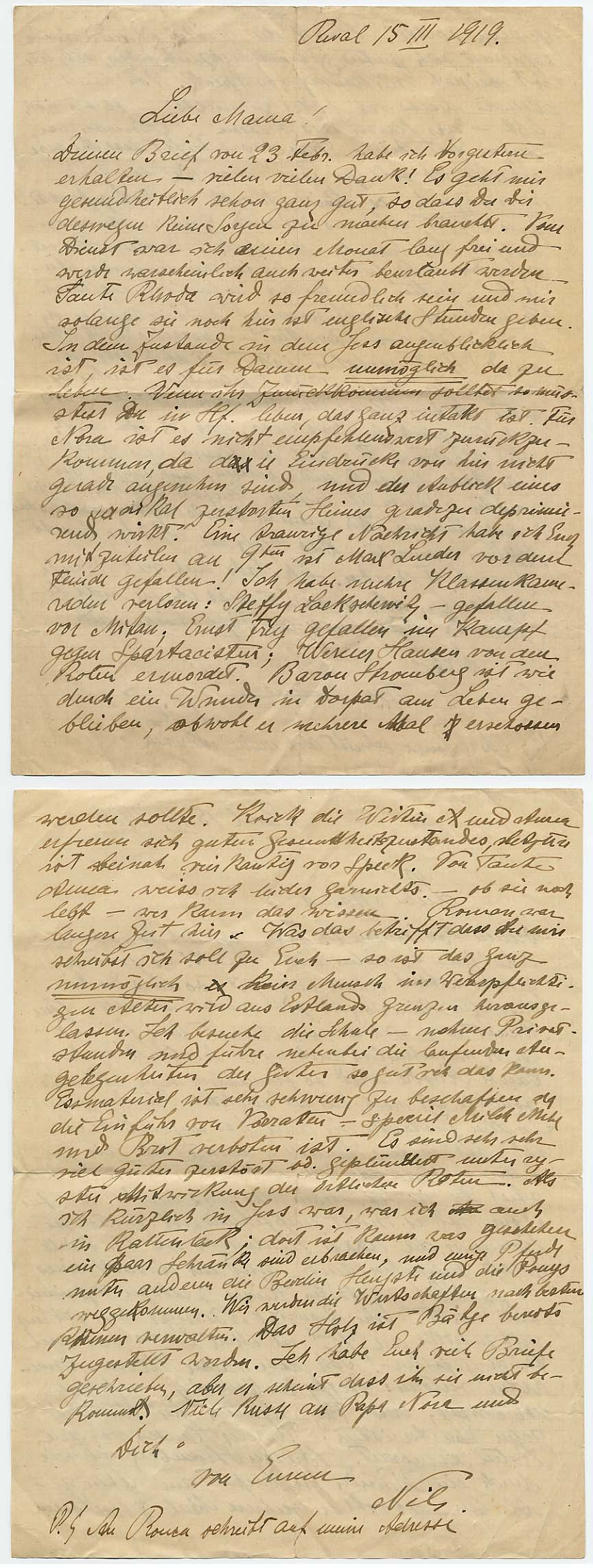

In a letter to his mom from March 15, 1919, 19-years-old Nils von Ungern-Sternberg being on vacation in Tallinn described the fate of his comrades and schoolmates:

I should convey you sad news, on the 9th fell Max Lueder. I have lost also some other classmates: Steffy Lackschewitz fell in Jelgava; Ernst Frey fell in a battle against Spartacists; Werner Hansen was killed by the Reds. Baron Strömberg miraculously survived in Tartu although he had been shot at several times.

Baltic Germans fought in the War of Independence on the Estonian side not only in the ranks of the Baltic Battalion. For example the youngest son of famous Count Berg, the lord of Sangaste Manor, served in the Northern Sons Regiment consisting of Finnish volunteers and participated at the battles on the southern front in winter 1919, amongst others also at the Paju Battle on January 31, 1919. Ermes Friedrich von Berg (1880–1949) had gone to live in Finland in 1917. For his service he was awarded the Cross of Liberty.

The photo of Ermes von Berg with his comrades has been taken in Valga on February 9, 1919.

On December 2, 1928, a memorial stone of the Baltic Battalion was opened in front of the house of German Cultural Self-Government in Tallinn. The memorial was removed in the Soviet period but restored to its place in the 1990s. Nowadays the building houses the Academy of Sciences (Kohtu 6).

Photo from the book: Heldengedenkbuch des Baltenregiments. Gesammelt und bearbeitet von Georg v. Krusenstjern. Tallinn, 1938

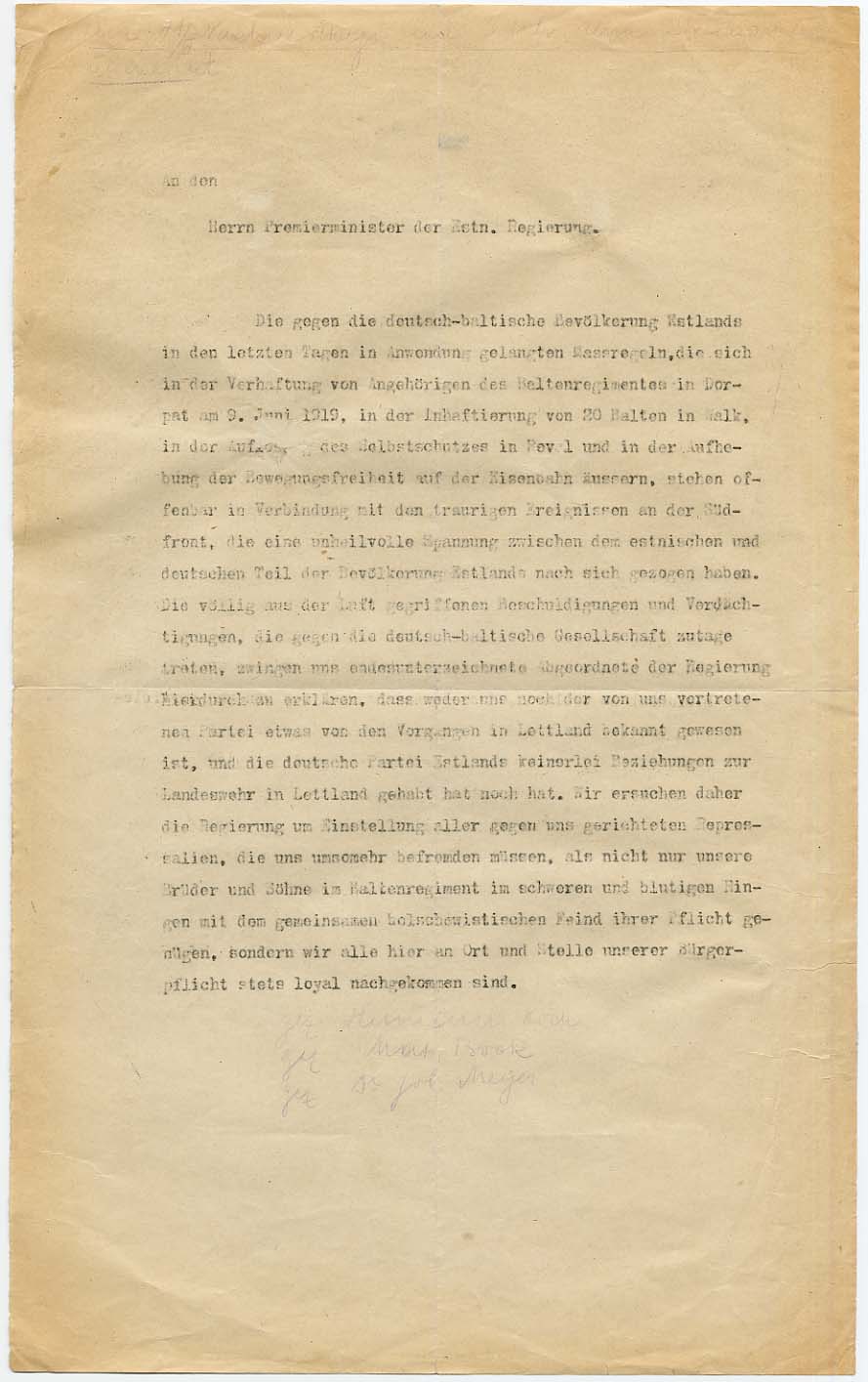

In summer 1919, the members of the German Party in the Estonian Constituent Assembly gave a petition to prime minister Otto Strandman demanding the end of the persecution of Baltic Germans. They thought that the reasons for arresting Baltic Germans in Tartu and Valga, the dissolution of German militia squad in Tallinn and restricting free movement on the railway was a combat on the southern front which caused disastrous strain between Baltic Germans and Estonians. To diffuse any doubts about their credibility, the deputies confirmed that they had no relationships with the Landeswehr, reminded of the participation of the Baltic Battalion in the fight against the Reds and stressed their loyalty to the new state.

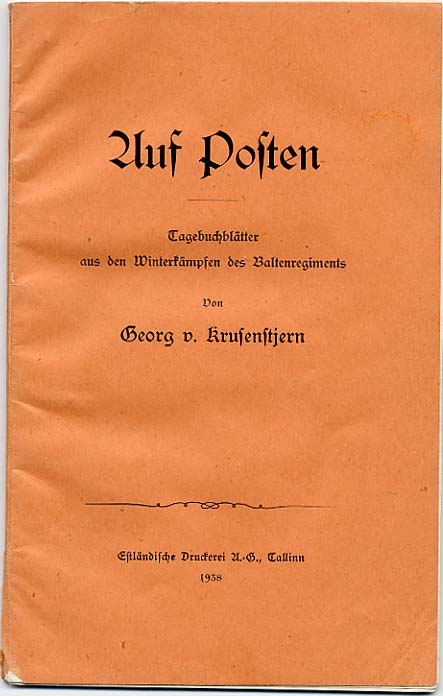

Son of the lord of Järlepa Manor, Georg von Krusenstjern (born in St Petersburg in 1899) served as a volunteer in the Baltic Battalion from 1918–1920. After the war he worked as a clerk in the paper and pulp mill in Tallinn. Krusenstjern also dealt with the history of the Battalion and published his war-time diaries.

In his earlier diaries, Krusenstjern observed the Estonian struggle for independence with rather contradictory feelings. On November 15, 1918 he writes:

The Provincial Assembly will convene on the 20th. The Estonian provisional government, the republic, which was proclaimed at the time of Germans’ arrival and now has a new start, seems to be almost overthrown… The Prime Minister Poska has been removed from office already! Yah, unfortunately there is a strong turn to the left again! Estonians behave very arrogantly and not as my father had hoped that they would involve us or ask help from our men – they do not want to know anything about them and would like to harm them wherever they can. German teachers and schoolmasters have been removed from office and German schools closed!

No one knows how it ends!

Georg von Krusenstjern’s memories of the combat of the Baltic Battalion on the Viru front in January and February 1919.

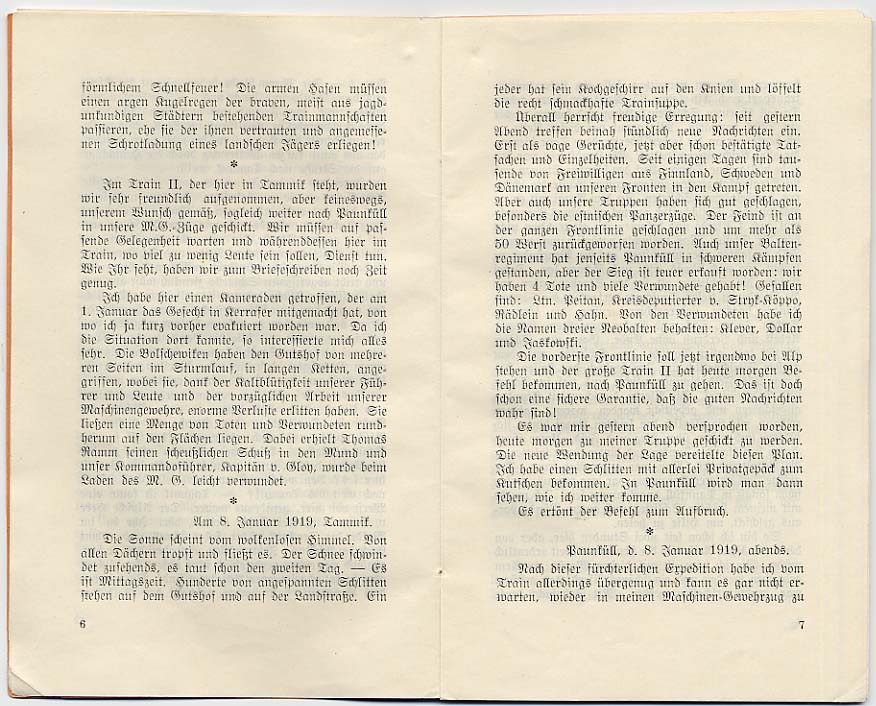

On January 8th, on the manor of Tammiku Krusenstjern noted in his diary:

Sun shines in cloudless sky. Snow is dripping from the roofs. Snow melts at noticeable speed, the thaw has lasted two days already.

It is lunch time. Hundreds of sledges have been gathered in the manor and on the road. Every soldier holds his cooker on the knees and sips rather well-made soup from it.

There is merry excitement in the air: since yesterday evening almost every hour we have received news. At first these were only vague rumours but now we have confirmatory facts and details already. Few days ago, thousands of volunteer soldiers from Finland, Sweden and Denmark have come to fight on our front. But our forces have done well too, especially Estonian armoured trains. On the whole front the enemy has been driven back and forced to retreat more than 50 versts (ca 53 km). Also the Baltic regiment has fought heavy battles near Paunküla. Our victory came at a high cost: four are dead and many wounded.

Auf Posten. Tagebuchblätter aus den Winterkämpfen des Baltenregiments von Georg v. Krusenstjern. Tallinn, 1938, S. 6-7.

In September, in the course of demobilization the War Ministry of Estonia decided to dissolve the Baltic Battalion. In the decree of September 20, 1920, on dissolution of the Baltic Battalion Colonel Constantin von Weiss wrote:

An epoch in Baltic German history at which future generations can proudly look back has come to its end with it […]

Having learned from his defeats and failure, our enemy surrendered in the hopeless fight and agreed to peace talks which ended with signing the Tartu Peace Treaty so honourable to us. Our homeland has been saved and we who have served in the Baltic Battalion can proudly look at our participation in the War of Independence.

The Constituent Assembly

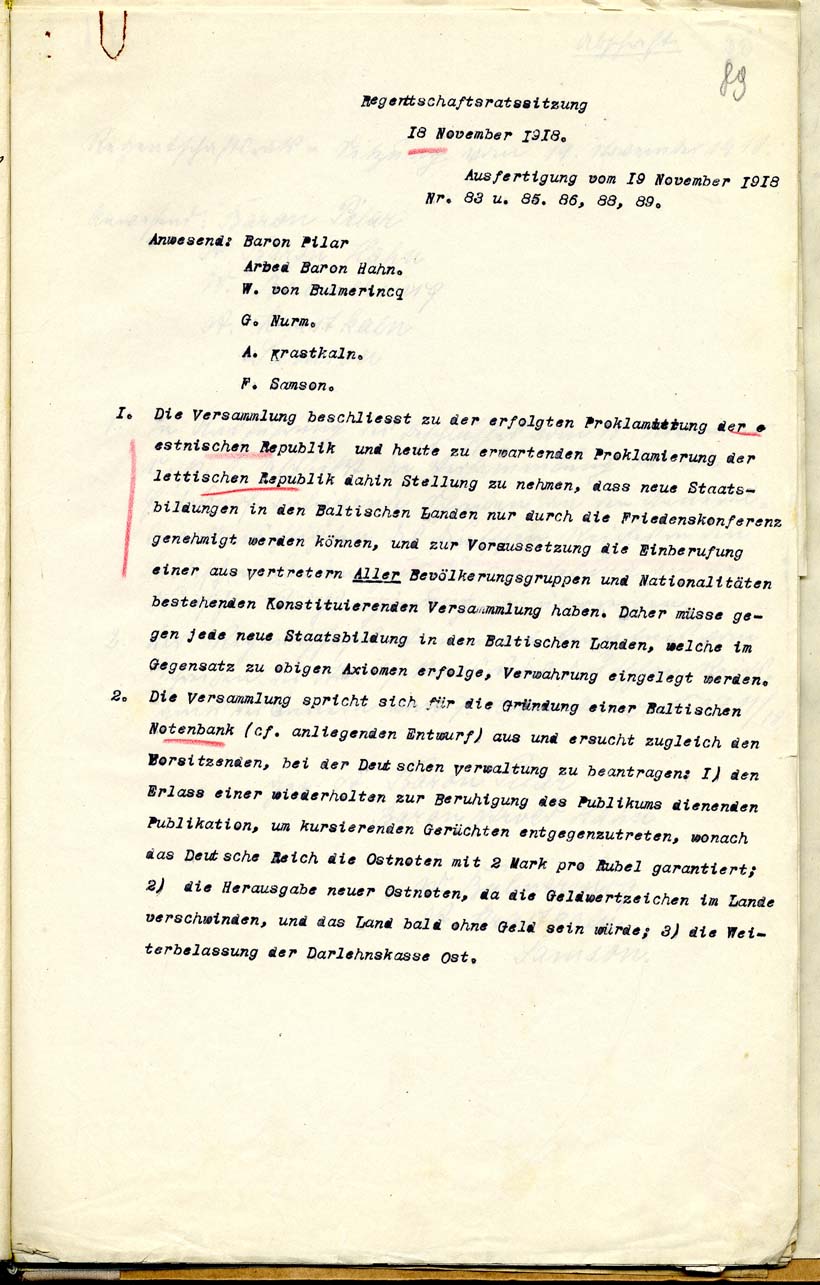

By the terms of the supplementary accord to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed in Berlin on August 27, 1918 Russia renounced its sovereignty over the territories of Estonia and Latvia and Germany undertook to determine the final status of these areas in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants. Baltic Germans could not rejoice over it long. On November 3, revolution broke out in Germany and six days later a new government headed by the leader of social democrats was set up. The new German provisional government’s representative in the Baltic provinces handed over power to the Estonian Provisional Government in Riga on November 19. It shook the ground under the feet of the advocates of a Baltic duchy. A day earlier the Baltic Regency Council formed in Riga in November had decided that the new states have to be approved by the peace conference and this requires the convening of the constituent assembly representing all the social and ethnic groups .

Resolution of the Baltic Regency Council of November 18, 1918, on determining the future status of the Estonian territory at the peace conference and the convening of the Constituent Assembly. Latvian National Archives. LVVA.4038.2.490, f. 89

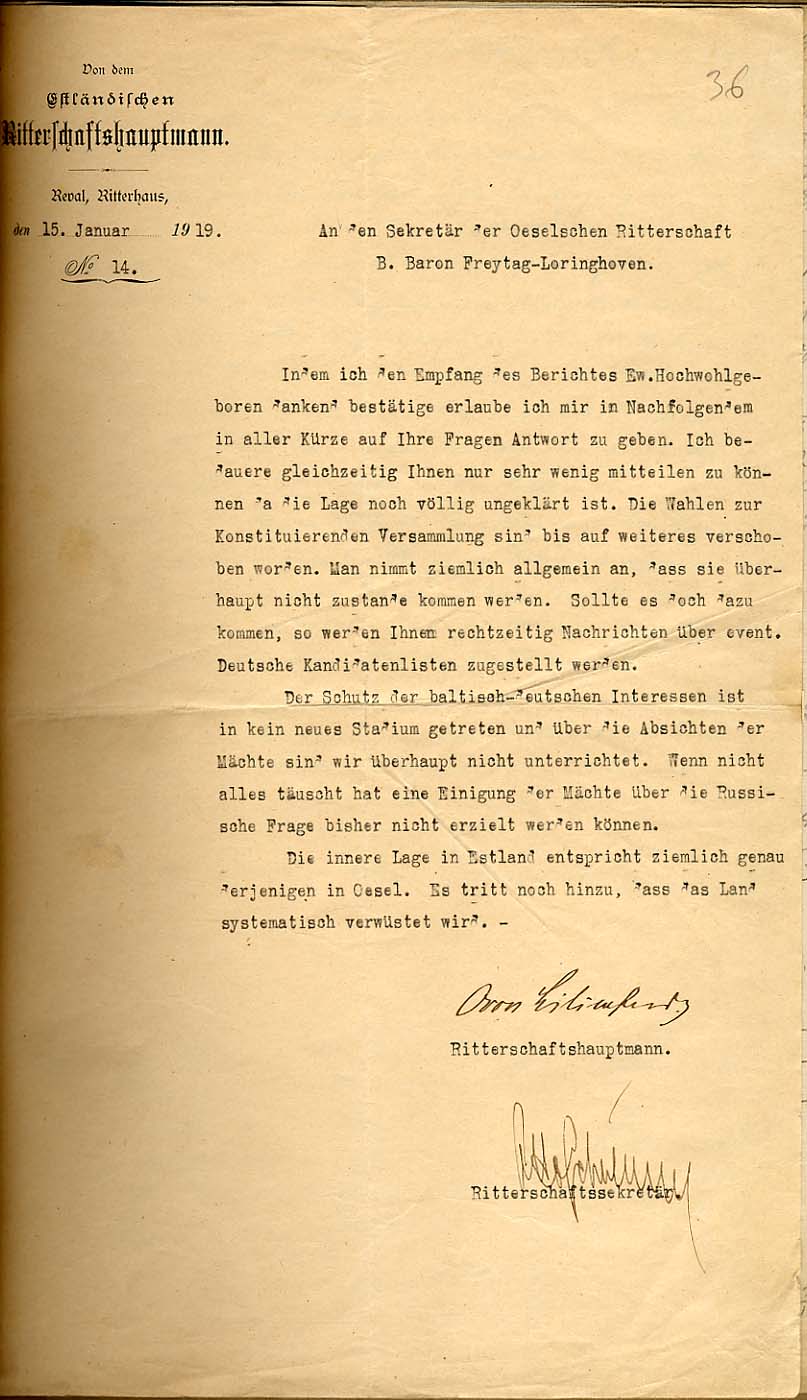

On January 15, the head of the Estland noble corporation Otto von Lilienfeld informed the secretary of Ösel noble corporation Burchard von Freytag-Loringhoven about the situation on the mainland. The country was devastated, Russian question was still unsolved, elections to the Constituent Assembly had been postponed and perhaps will not take place at all. There is nothing to add about the protection of Baltic German interests as we have no information about the plans of the great powers.

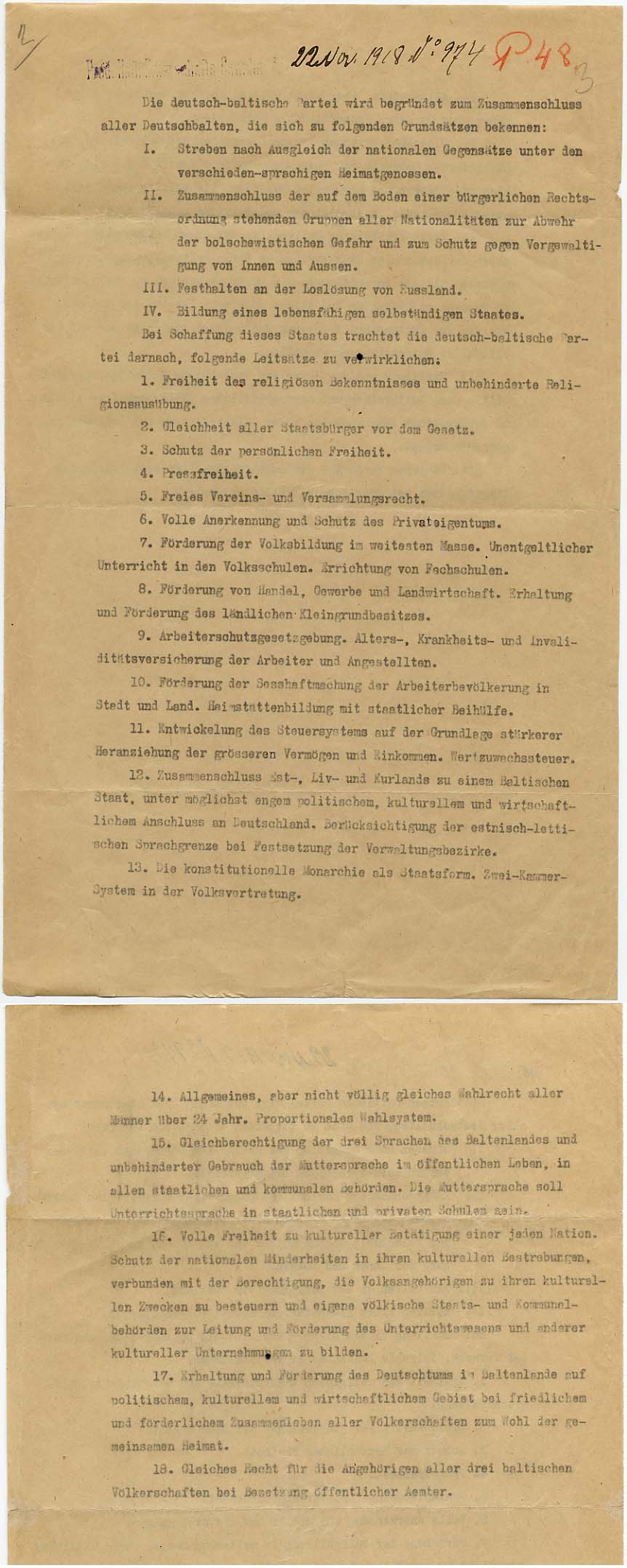

The German-Baltic Party in Estonia was established on December 23, 1918. Preparations for establishing a new party had started in September. The program drafted in November advocated a united Baltic state with constitutional monarchy and bicameral assembly.

Christoph Friedrich Carl Mickwitz (1850–1924), leader of the German-Baltic Party, journalist and poet. Stammtafeln nicht immatrikulierter baltischer Adelsgeschlechter. Band I, Lieferung 3–4. Bearbeitet von Alfred von Hansen. Reval 1933.

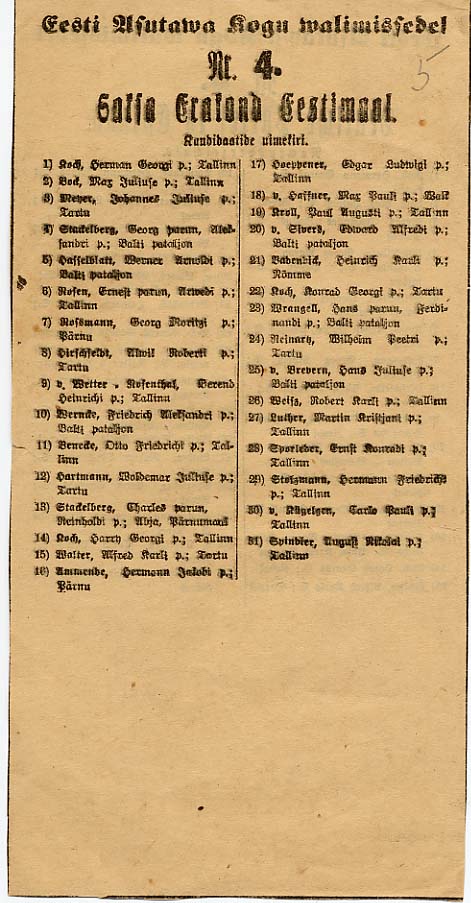

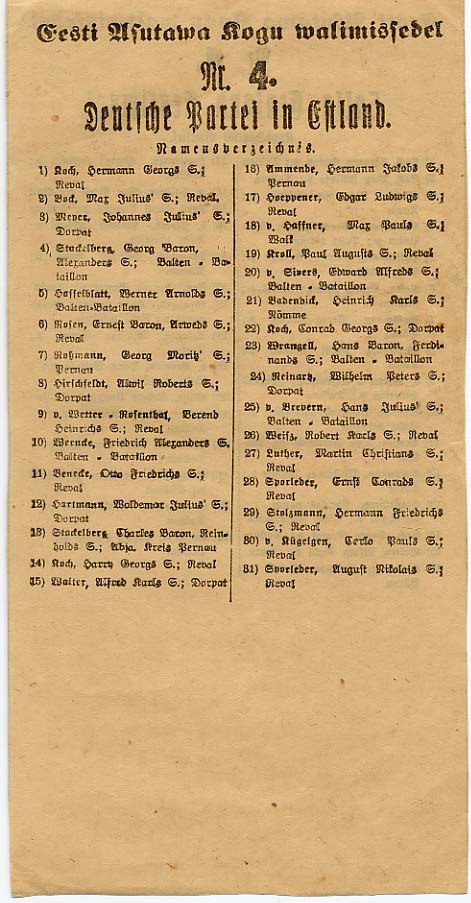

The list of the German-Baltic Party’s candidates at the elections of the Estonian Constituent Assembly in April 1919

Three candidates of 31 were elected to represent German minority in the Constituent Assembly: gynaecologist Johannes Meyer from Tartu; lawyer and the deputy of the Estonian Provincial Assembly in 1917 Max Bock and lawyer Hermann Koch. In all the candidates received 11,462 (ca 3%) votes.

Kadri Tooming, archivist

Translation to English: Kersti Lust

![Eduard von Dellingshausen. Kodumaa teenistuses. Eestimaa Rüütelkonna peamehe mälestused, [Rüütelkonna tegevusest 19. sajandi lõpus ja 20. sajandi alguses]. Tallinn, 1994 Im Dienste der Heimat! Erinnerungen des Freiherrn Eduard von Dellingshausen ehem. Ritterschaftshauptmanns von Estland. Stuttgart, Ausland und Heimat Verlags-Aktiengesellschaft, 1930](http://blog.ra.ee/wp-content/uploads/im_dienste.jpg?w=547)