While collecting data for the database “Land registers”, I have sometimes come across rather unexpected stories.

Two decades before the Great Northern War, the Swedish King Charles XI initiated the Great Reduction of manors in the overseas provinces of Estland and Livland. About 80 per cent of all noble holdings in Livland and c. 50 per cent in Estland went into the crown possession. The war ravaged the provinces in 1700-1710 and the plague also took its toll. The human loss was huge, villages were suffering population decline or even became empty. Several manors were also damaged or desolated and their owners had either died or fled the country. Some parishes had no pastors who would have recorded the deaths of parish members in the registers. As a result of the war, Sweden lost Estland and Livland to Russia and the Russian Tsar Peter I restored landholding rights that had existed before the reforms of Chrales XI of Sweden. In the “unsettled times” after the war, hunt for ownerless landed properties started. In such a situation, minor heirs could even lose their noble title as well as their title to land, as the case of the descendants of Rittmeister and Baron (Freiherr) Heinrich Homburg shows.

On June 28, 1821, the bailiff Heinrich Homburg, on the behalf of himself and his relatives Lause Tönnise Michele Michel, Lause Tönnise Michele Maddis, Lause Michele Tönnise Maddis and Lause Hindriko Jurry Jaan, filed a lawsuit to the Estland Supreme Land Court against the owner of Saastna (Sastama) Manor, the district magistrate Andreas Peter Friedrich von Rennenkampff, claiming the restoration of their title to former Lesenow Manor, located in Hanila Parish, which had once belonged to their great grandfather (Urältervater), Swedish Rittmeister and Baron Heinrich von Homburg.

In his application, he mentions that in 1766 a case had been started already by someone who could not proceed with it due to lack of money. In 1816, Heinrich Homburg asked the feudal court of Läänemaa (Wiek) to set the Homburg’s descendants living at Saastna Manor free and restore them their old family name. Few weeks later, he submitted a claim to return to them also Lesenow Manor in its Swedish time boundaries, including besides manorial lands also six farmsteads in the village of Tauko and two farmsteads in the village of Salevere (Sallofer).

Lesenow Manor bordered on Saastna Manor. After the death of Baron Heinrich von Homburg, the manor was given to his son, Baron Claus von Homburg, who died in the time of war and plague, leaving two minor sons Heinrich and Georg as successors. Peasants took them into their households and raised them up. Only the byname Lause derived from the German name Claus reminded the former ‘noble’ origin of the peasants called Jürri and Hinrich.

Heinrich Claus Homburg’s or Lause Hinrich’s descendants were personally free until 1752, when the lands of Lesenow Manor were attached to Saastna Manor. In 1784, his grandson, Heinrich Homburg, gained personal freedom again.

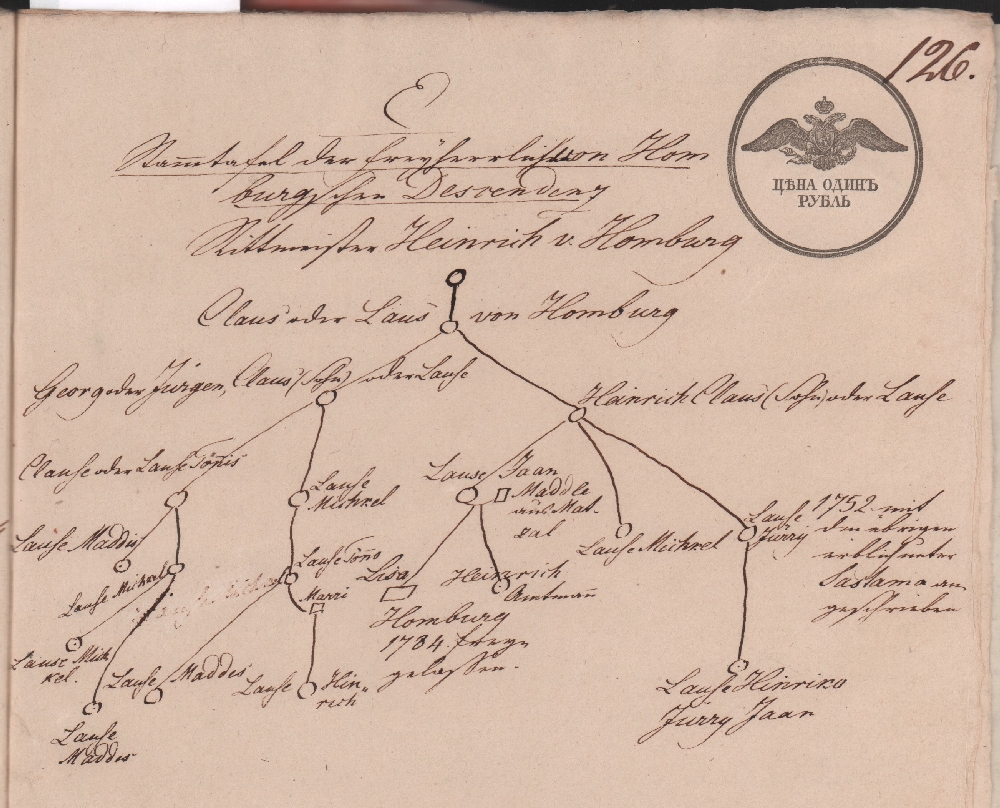

Family tree of Hans Homburg. RA, EAA.858.1.2579, l 126

A myriad of obstacles stood in applicants’ way. In the end, they managed neither to prove their noble origin nor get back the landed property as over a hundred years had passed since their loss. The evidence could be good and abundant but it was still insufficient.

From the evidence presented to the court, it appears, for example, that there really had been a manor house at Lesenow but at the beginning of the nineteenth century there were only ruins covered by vegetation. In the parish church of Hanila, there were also a tombstone of the Homburgs and a wooden coat of arms with an inscription «Homburg Erbenherr von Lesenow Anno 165… geboren». The pastor of Hanila church, Ernst Lüdig, confirmed: «The documents show the locations of the burial sites of some noblemen in the church. For example, we know where the owners of Virtsu and other manors have been buried. Also the Homburgs had their burial site here.»

During the court proceedings, however, several questions remained unsettled. Perhaps the place called Lesenow was not located in the parish of Hanila? Perhaps Homburg was just a traveler passing through? The Consistory ordered the Hanila pastor Diedrich Püschel to make copies of preserved documents. It was a difficult task as part of the parish registers had been demolished by fire. The parish register of Lihula (Leal) has survived from 1766. A document from this year also confirms that the church wardens of Hanila, Captain Krüdener and Captain Pistolkohrs, had had to reply to the request by the lord of the Manor of Saastna, Friedrich Daniel Stackelberg, who wanted to become for one Riksdaler the owner of the burial site of the Homburgs located in the choir, since the descendants’ right to it ‘had expired long ago’. It is the same Stackelberg who in 1784 set free Heinrich Homburg and his sister Liisa.

During the proceedings, three different versions of the family tree of the Homburgs-Lauses were drawn. An excerpt from the inventory of peasants’ duties from 1685 was also added to the evidence.

The jurymen noted that that the place name Lesenow could have been replaced by Ullast as several old village and manor names had ceased to exist and had been replaced by new ones. They also agreed that the tomb stones and the coat of arms are more reliable evidence than records which can easily be forged. They admitted that the boys of Homburg were raised by peasants since in the aftermath of war and plague, not many were willing to become guardians of orphans. After the unification of Estonian areas with the Russian empire, the descendants of the Homburgs lacked sufficient resources to fight with the influential and prosperous noble families and claim their property rights.

Stackelberg, the lord of Saastna Manor, could not foresee that the man whom he sets free will start a long-lasting lawsuit. It is unclear how Heinrich Homburg handled the complicated and expensive matters. His position as a bailiff at Harku Manor as well as the purchase of a house in Tallinn show that he most probably was not just a humble peasant. Homburgs were not miracle-men’ and they were obviously backed by some knowledgeable men.

The laws and the socio-economic configuration at that time did not allow the «historical justice» to be restored. The above-mentioned peasants (Michel, Jürri, Madis and Tönnis) were set free along with other serfs in the gubernia of Estland who gained freedom step by step over the period of 14 years. In 1828, the district magistrate of Ranna-Läänemaa (Strand-Wiek) claimed that the parish court of the Karuse-Hanila had not held any sessions for two years since its chairman had been missing. Lesenow Manor remained in the possession of the lord of the Manor of Saastna as before.

[Estonian version of the blogpost]

Reet Hünerson, specialist at the National Archives of Estonia

Translation into English: Kersti Lust